The DNA of Big Ideas

The DNA of Big Ideas

A Small Business Survival Guide, From Ancient Silk Roads to Silicon Savannahs

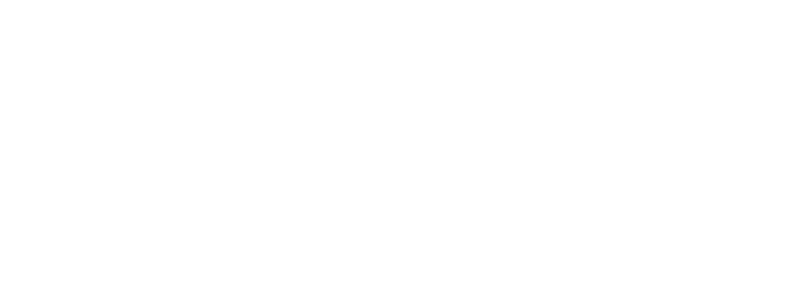

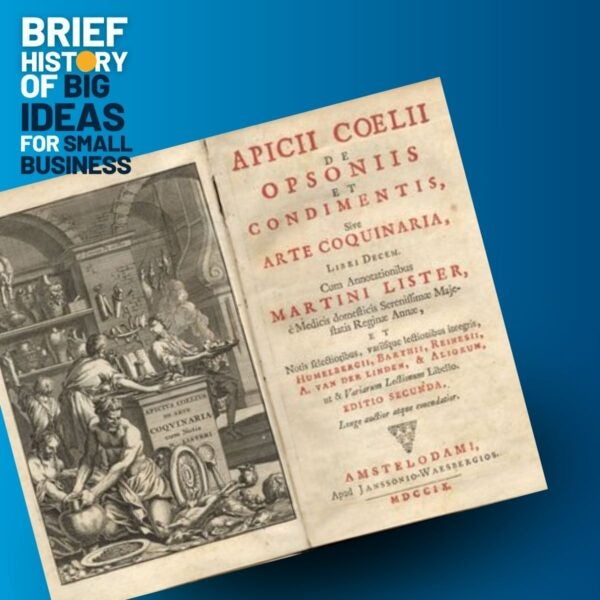

In the heart of Timbuktu’s 14th-century marketplace, Ashamur, a Tuareg merchant of the Tademakkat clan, leads a camel caravan laden with salt from the Sahara’s mines. He has struck a deal with a Berber trader for gold and ivory. Two hundred years later, in Edo-era Japan, a daughter of potter Sakaida Kakiemon named Okiku meticulously crafts delicate porcelain jars and plates sought after by the shogun’s court and European traders. Almost one millennium before Ashamur, Marcus Gavius wanders through Rome’s populous Forum, peddling exotic spices, and one millennium after Okiku, a lone coder is bent over a laptop in her San Francisco studio–set in a garage, of course.

An invisible thread of entrepreneurial DNA links Ashamur, Okiku, Marcus Gavius, and the coder, despite being centuries and worlds apart. Their success, across millennia, hinges on a code as timeless as it is adaptable, and it’s common to all the big ideas that transcend time and place.

Scratch an itch, solve a problem. Ashamur, sensing a demand for salt in the gold-rich south, forged a trade route that would give him high status within his prosperous clan. His exchanges were only possible thanks to the invention of the camel saddle by ingenious Tuareg riders. According to an 1858 historical account by traveler Heinrich Barth—Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa—the camel saddle was a creative hack that allowed long-distance travel over the desert and the emergence of trans-Saharan commercial routes.

Over millennia, sitting tall over their dromedaries, nomad traders like Ashamur challenged the elements of a vast and inhospitable territorial space, opening a market for thousands of small business entrepreneurs. Over the Camel humps, sort of FedExs and Ubers of the ancient desert, nomad traders built an entire ecosystem of oases and travel services to serve the growing trade.

The talented Japanese artisan used her unique command of Chinese and Portuguese to leverage the rising popularity of tea ceremonies and the growing demand for Japanese porcelain by the Dutch. With her extraordinary business acumen, she opened the doors to an international market and transformed the already respectable family business into a transnational force and one of the few economic activities where women were allowed to venture (Patricia Fister, Japanese Women Artists 1600-1900).

Roman gourmands craved cinnamon from Ceylon? Gavius delivered. Today’s consumers yearn for a seamless app experience? The coder in the garage is on it, so the Kenyan entrepreneur can make a mobile payment app to address the lack of banking infrastructure in rural villages. It’s simple: find a need, fill it. Fads fade, but meeting a genuine need is the path for businesses that can last like a sturdy camel saddle.

Next, don’t fear the newfangled. Embrace the tools of your time. Ashamur’s camel caravans were the FedEx of the Sahara. Okiku’s kiln, a technological marvel of its day. Rome had its abacus, we have our algorithms, cloud computing, AI, and social media to give small businesses an edge. The medium changes, the message remains: adapt or perish. It’s not about being a tech whiz, but recognizing that each era’s tools can be harnessed to amplify one’s impact.

Next, don’t fear the newfangled. Embrace the tools of your time. Ashamur’s camel caravans were the FedEx of the Sahara. Okiku’s kiln, a technological marvel of its day. Rome had its abacus, we have our algorithms, cloud computing, AI, and social media to give small businesses an edge. The medium changes, the message remains: adapt or perish. It’s not about being a tech whiz, but recognizing that each era’s tools can be harnessed to amplify one’s impact.

Think beyond your borders. Ashamur’s network spanned the African continent. Gavius’s spices came from across the known world. Kakiemon porcelains graced tables in Kyoto, Edo and Amsterdam; the coder’s app could be downloaded anywhere with an internet connection. Today, a Chilean winemaker finds a market in China, and a Nigerian fashion designer sells on Etsy. Whether it’s sourcing or selling, a global mindset expands horizons. The world is your oyster, if you dare to shuck it.

Empower people, reap the rewards. Ashamur’s loyal caravan drivers were the backbone of his business. Okiku’s apprentices ensured the continuity of her craft. Today, a motivated team, whether in-house or freelance, is a startup’s most valuable asset. Today, user-generated content and passionate fan bases can catapult a small business into the stratosphere.

“Be water, my friend. Water can flow or it can crash,” but it always makes its way through cracks, used to say the martial arts icon and cinema entrepreneur Bruce Lee. Not a fan of Kung fu? Try Zen wisdom: Be resilient, like bamboo in a typhoon.  Adaptability is essential. Markets change, empires fall, pandemics hit. Those who adapt, like Gavius pivoting to new trade routes when the old ones closed, are the ones who succeed. Ashamur navigated shifting political alliances, Okiku weathered economic downturns. Today, small businesses pivot online, offer delivery, and reinvent themselves. It’s not about being unbreakable, it’s about bending without breaking.

Adaptability is essential. Markets change, empires fall, pandemics hit. Those who adapt, like Gavius pivoting to new trade routes when the old ones closed, are the ones who succeed. Ashamur navigated shifting political alliances, Okiku weathered economic downturns. Today, small businesses pivot online, offer delivery, and reinvent themselves. It’s not about being unbreakable, it’s about bending without breaking.

This DNA of big ideas isn’t just ancient lore or Silicon Valley buzzwords and tech-bro platitudes. It’s a survival guide for every corner store, every food truck, every online shop. These aren’t just “small” businesses; they’re the economic arteries, the cultural capillaries, the beating heart of our communities.

By understanding the forces that have shaped this communal cardiovascular system, from Timbuktu’s salt caravans to Tokyo’s tea houses, from Roman marketplaces to Silicon Valley incubators, we unlock small and growing businesses potential to not just weather storms, but to thrive in the bazaar of the modern world, the ever-evolving global marketplace.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of ANDE.