Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) Asia has continued its commitment to building inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystems through the Access and Learning Opportunity Learning Lab, a dedicated platform for a cohort of 20 entrepreneur support organizations in the Asia region, which supports the implementation of disability and gender inclusion measures within their organizations.

Following the launch of the lab, ANDE Asia recently conducted the first session of the lab focusing on “Exploring Intersectionality and Designing Inclusive Programs”, where the cohort explored the concept of intersectionality and its importance in business development programming from the two invited expert speakers; Shamha Naseer, Gender Specialist for the Youth Empowerment Portfolio in Asia and the Pacific at UNDP’s Bangkok Regional Hub, and Ian Jones, Co-Founder and Director at Mekong Inclusive Ventures.

During the session, the cohort members also shared their insights on intersectionality and discussed their experiences working with stakeholders who face compounded or heightened barriers due to overlapping identities, and highlighted best practices for fostering inclusive leadership and decision-making within their organizations.

- Highlights from Shamha Naseer

- Why should intersectionality matter for us?

- Challenges for Intersectional Programming

- Enablers for Intersectional Programming

- Key Takeaway

- What are Compounded Barriers?

- What is Inclusive Programming?

- Process guidelines for inclusive decision-making

- Reasonable accommodations for inclusive decision making

Shamha began the session with a warm-up exercise, consisting of a short introduction round, where participants were requested to use three words that describe their identities. Once these characters were identified, she asked the participants to think about two specific questions to help the participants recognize that everyone carries multiple identities and how this influences how we experience power, opportunity, and also how we encounter barriers:

- Which of these identities gives you privilege and power in certain settings?

- Which ones create barriers or make you feel invisible?

With her presentation, she aimed to explore the concept of intersectionality and show how overlapping identities create layered discrimination and sometimes even hidden barriers. Shamha’s session explored intersectionality as more than a theory but as a practical tool to support marginalized individuals and groups. She emphasized that people’s identities, like their gender, disability, age, ethnicity, and geographical location, don’t exist in isolation but intersect, creating complex layers of disadvantage or privilege. The session highlighted the importance of acknowledging that these identities don’t exist in silos; they overlap, and when they overlap for certain individuals and groups, they can create heightened barriers.

For instance, in the Asia-Pacific region, over 400 million people live with disabilities, many of whom are women and girls. These women already face gender-based obstacles, and when factors like disability, rural location, and age are added, the barriers compound. Shamsha illustrated this with a hypothetical example of a young woman with a disability from a rural village, who might face issues like inaccessible transport and cultural stigma, all at once. Intersectionality helps us understand and address these overlapping challenges more effectively.

The session continued by addressing the question: Why should intersectionality matter to us?

Many programs focus on a single identity, for instance, on youth or persons with disability, or even young women, but miss out on those identities that might be intersecting. For example, women with disabilities who face more complex barriers are often excluded because these programs don’t take into account the heightened barriers that these individuals or groups may face when these social identities intersect, and are therefore, unintentionally left out.

A report by UNESCAP illustrates that people with disabilities are approximately two to six times less likely to be employed than persons without a disability in the region, and women with disabilities are only half as likely as men with disabilities to find a job. This shows that exclusion is not due to a single identity but the intersection of multiple factors.

Systems of Power and Invisible Barriers

Systems of Power and Invisible Barriers

Shamha highlighted that even when programs appear open to all, at times, systems of power often create visible and invisible barriers that limit participation, especially for those with intersecting identities. For example, requirements such as proof of employment or formal education for grants may exclude young women with disabilities who have never had access to these opportunities. These forms of exclusion are often not deliberate but stem from a failure to recognize the diversity and lived experiences within communities.

Barriers can also be structural, such as inaccessible applications, physical spaces, or program formats, and attitudinal, rooted in biases around who is considered a “successful” entrepreneur. Assumptions that entrepreneurs must work full-time or be free of caregiving responsibilities can further marginalize women and persons with disabilities. Addressing these barriers requires a conscious effort to recognize and dismantle both structural and unconscious biases across the ecosystem.

To be truly inclusive, programs must be co-designed to reflect the lived realities of these intersecting identities. From design delivery to evaluation, it is crucial to ask: Who is missing from the program/our outreach? Who is silently opting out because the program wasn’t built for them? What overlapping barriers are they continuing to face? How can we design support that addresses the complex realities of their lives?

This requires taking a step back and seeing the full picture to see how different barriers overlap.

- Limited representation: Across different ecosystems, persons with disabilities, especially women with disabilities, are rarely included in leadership roles, whether it be for policy or program design, whether it be in decision-making processes at different stakeholders.

- One-dimensional policies and programs: Narrow program designs, meant for an imaginary ‘average beneficiary’, often leave behind those at the intersection of these different identities.

- Inflexible systems and structures: The rigid requirements around educational criteria, inaccessible formats, etc., can unintentionally exclude people. Imagine having a pitch competition, and the criteria being the submission of a written proposal only. Even though this is not intentional, it can continue to exclude certain individuals and groups.

- Complexity of Measurement and Accountability: There are, of course, challenges in collecting data, but it’s important to collect disaggregated data by gender, age, and geographical location. Once you have this data, you have to analyze it through an intersectional lens.

- Cultural and Social Norms: This can prevent and limit the participation of individuals and groups. For example, in some communities, people with disabilities continue to be stigmatized, and women’s mobility is restricted. These intersecting norms also shape who is able or safe to take entrepreneurial risks or pursue entrepreneurship opportunities.

- Risk of oversimplification: Intersectionality is a very complex issue. We acknowledge that it’s also about understanding how the power structures shape the lived realities of individuals.

Shamha concluded by outlining key enablers that can drive more inclusive, intersectional programming, particularly in the context of entrepreneurship support:

- Centering Marginalized Voices: Programs must ask whose voices are prioritized and who might be left behind. Upholding dignity, choice, and autonomy means giving individuals the freedom to pursue entrepreneurship on their terms, with access to clear information and options.

- Universal Design: Build inclusivity into the design from the start. This includes removing barriers—physical, transportation, and communication—and involving diverse perspectives early in the process to ensure accessibility for all.

- Diverse Knowledge and Teams: A truly inclusive program is co-designed with diverse communities. This means recruiting and retaining a wide talent pool and consulting with marginalized groups to ensure programs remain relevant, adaptable, and effective.

- Relational Power: Equity in partnerships and within organizations is key. Recognizing and shifting power dynamics allows for meaningful collaboration, where marginalized individuals are not just participants but co-creators with influence.

- Contextual Awareness: Privilege and disadvantage are fluid and context-specific. What’s inclusive in one country or generation may not be in another. Programs must remain flexible, adaptable, and tailored to local realities.

- Meaningful Inclusion Takes Time: There’s no quick fix. Real inclusion requires intentionality, small practical steps, and a commitment to learning and adjusting continuously.

Intersectionality helps us understand how overlapping identities shape people’s access to resources and opportunities. It is important to have a program or initiative service that is adaptable to the evolving context and to the needs of, for example, young entrepreneurs that you are engaging with. Building a truly inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystem demands intentionality and flexibility. This would involve redesigning policies, practices, and structures to center equity, dignity, and justice at the core of all our work. Following Shamha’s introduction to the topic, Ian Jones elaborated on the concept of compounded barriers.

When we look at compounded barriers, we’re talking about how two or more identity-based barriers interact to amplify exclusion beyond what each barrier could create alone. It’s more than just adding one plus one. What we see here are very unpredictable hurdles.

A real-life example was shared from Northern Cambodia, where the International Committee of the Red Cross supported people with disabilities in rural areas. Transport was a major barrier, especially in the rainy season. The solution was simple yet effective: adapting a lightweight, three-wheeled tuk-tuk for accessibility, offering an agile and inclusive approach to service delivery.

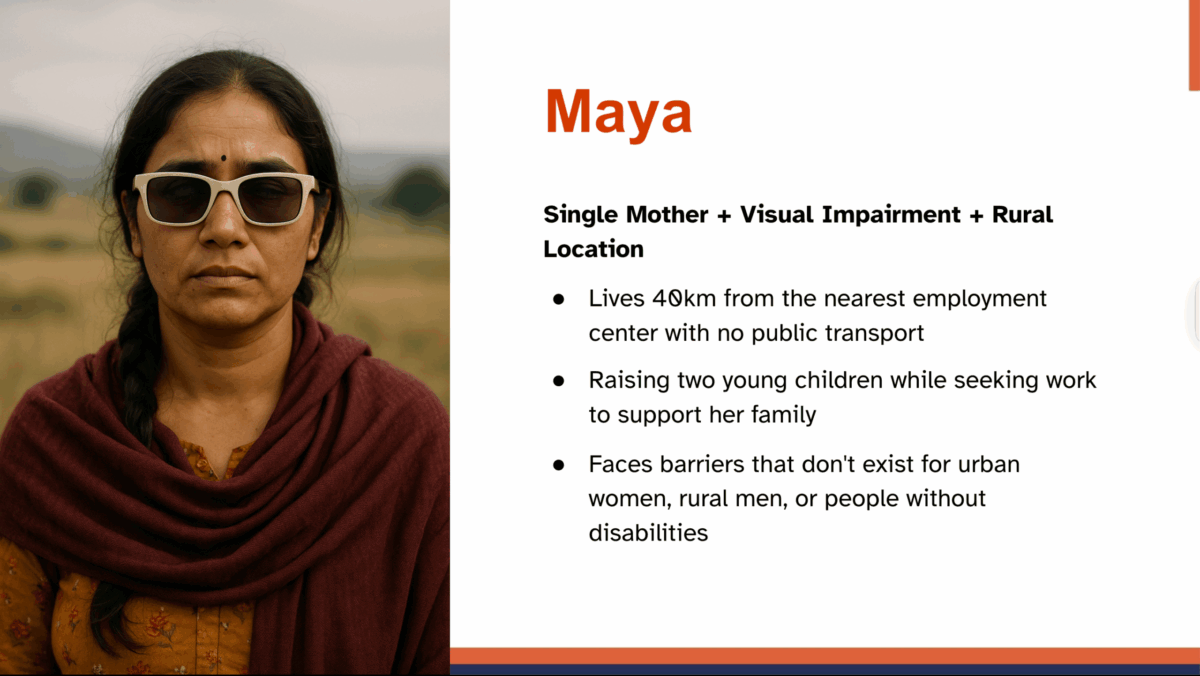

A persona-based approach helps illustrate this: for example, Maya, a single mother living 40 km from the nearest job center with two young children, faces challenges that urban women might not. Empathy and localized understanding are essential to making programs inclusive, not just in theory, but in practice.

What is the real cost—financial, physical, and emotional—for a woman entrepreneur with a disability to participate in a program? This approach reframes intersectionality from a theoretical concept to a practical, empathetic mindset, making it accessible and actionable for all.

Likewise, mental health is quite often a hidden disability. People with severe anxiety at times can struggle to leave the house. People with mental health episodes like schizophrenia sometimes struggle to even get the confidence to engage with society. How the community views mental health treatment is important because, in a lot of communities, there’s not even sufficient language around mental health and mental illness as a hidden disability.

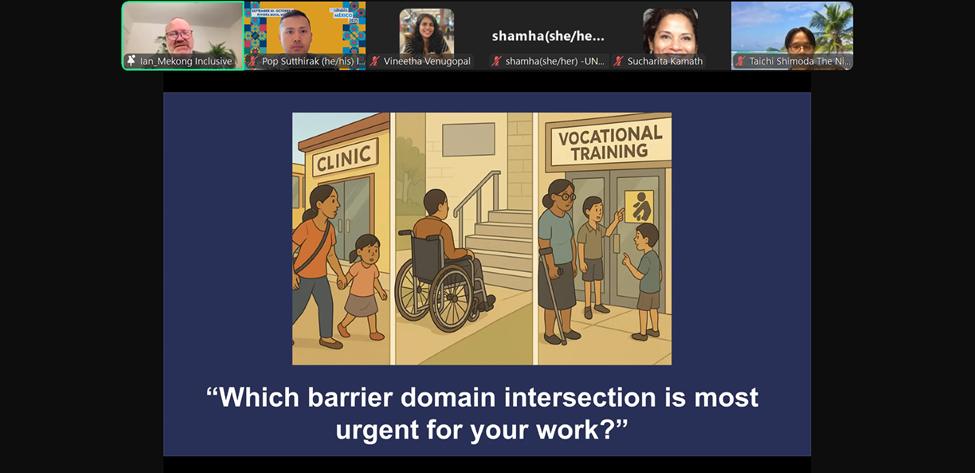

Ian emphasized that a key part of intersectional programming is educating systems and ecosystems about compounded barriers—those that arise from overlapping personal, social, and structural factors. He further outlined three key domains of barriers—access, stigma, and systemic—which intersect and compound exclusion for marginalized individuals:

Access Barriers include physical infrastructure, digital accessibility, and communication challenges. While many programs invest in surface-level inclusion (e.g., financing women entrepreneurs), they often overlook fundamental accessibility, such as web design or physical mobility.

Stigma Barriers are deep-rooted biases that marginalize people based on gender, disability, or identity. For instance, banks may deny loans to women with disabilities not due to policy but due to cultural bias.

Systemic Barriers result from policy gaps and fragmented services. These are often invisible but powerful, such as job training programs requiring online forms or adult shelters rejecting transgender clients.

Ian then used real-life personas ( with names and details changed) —Maya (a rural single mother), Ahmed (a refugee with mental health needs), and Alex (a transgender teen)—to illustrate how multiple barriers interact:

- Ahmed can’t afford transportation to a mental health clinic, the clinic lacks Arabic-speaking staff, and stigma in his community prevents him from seeking help.

- Alex faces age-related restrictions in youth shelters and stigma-based rejection from adult shelters. Systemic design failures cause anxiety and long-term harm as they age out of care.

The consequences of ignoring these barriers are severe: low program uptake, widening inequality, and worsening outcomes. Programs designed without intersectional insight often fail the most marginalized, like women with disabilities who have never been directly invited to participate.

Finally, he stressed that inclusive, universal design is not just ethical—it’s economically sound. Investing in accessible, systemic solutions early is far more cost-effective than retrofitting systems or dealing with the fallout of exclusion. Intersectional data collection, empathetic program design, and continuous system-level reflection are crucial to ensuring no one is left behind. It shifts from designing for a ‘typical’ user then accommodating others, to designing from margins outwards.

For instance, in job training programs, a single mother may face barriers that aren’t immediately visible. A simple needs assessment through a Google form won’t capture her reality. That’s why the team conducts phone interviews, asking about family responsibilities, including childcare. In cases where childcare is a barrier, they adapt program logistics, such as hosting training sessions at rural primary schools so mothers can bring their children. Other examples include providing session materials in multiple formats (audio, large print, plain language to accommodate different learning needs).

A program designed for Maya’s intersection ( rural + disability + single mother) would include remote participation options, flexible scheduling, and childcare coordination. These accommodations improved completion rates for all participants, including non-rural participants and those without disabilities. Thus, universal design works better for everyone, not just marginalized populations.

Ian also listed three core principles of inclusion:

- Intersectional participation: co-design with people from multiple intersections.

- Multi-access design: create multiple pathways to the same outcome rather than one size fits for all approach

- Flexible systems: build adaptability into program structure to respond to emerging intersectional needs.

He also stressed that implementing these might require reasonable accommodations such as providing interpretation services in multiple formats (live interpreters, video relay, written translation) to accommodate different communication preferences and disabilities and scheduling co-design sessions at various times and locations, including community spaces, to reduce participation barriers for different intersections.

The group also discussed the Inclusive Decision-Making framework, leadership behavior that builds inclusion, building trust across intersections, and building trust across intersections and suggested the following process guidelines and reasonable accommodations.

- Use structured processes that actively seek intersectional perspectives before making program decisions.

- Build in specific checkpoints to identify whose voices are missing and create pathways for meaningful participation.

- Intersectional Curiosity: Regularly ask “How might this impact different identity combinations?” rather than assuming universal experiences

- Process Transparency: Make decision-making systems visible and accessible to people from different intersections.

- Consistent follow-through on inclusion commitments matters more than perfect initial understanding of all intersections.

- Offer multiple ways to provide input (written feedback, recorded voice messages, one-on-one meetings) for people with different communication styles and comfort levels.

- Provide decision-making materials in advance and accessible formats, allowing extra processing time for people with cognitive differences or language barriers.

- Send meeting agendas and materials 48 hours in advance with clear objectives, allowing participants to prepare and participate meaningfully.

- Use multiple communication methods during meetings (verbal discussion, chat function, written responses) to accommodate different participation styles and disabilities.

- Create multiple feedback channels (anonymous surveys, peer advocates, ombudsperson), recognizing that people may feel unsafe giving direct feedback.

- Establish clear timelines for addressing concerns and provide regular updates on progress, accommodating different needs for communication frequency and transparency.

This approach shows how real inclusion involves understanding barriers beyond the most visible ones and addressing them. The Access and Opportunity Learning Lab thus advocates for a systemic and universal design approach. By designing for everyone—from women, individuals with disabilities, gender minorities, to entrepreneurs from rural areas—the result is broader, more meaningful access and participation.