There is little debate that the climate impact measurement and management (IMM) field is an unsettled space, with many actors attempting to navigate and codify various frameworks, principles, and metrics. As surfaced in the August 2022 guide by ANDE and Climate Collective titled Measuring the Impact of Climate Small and Growing Businesses: A walk-through of impact tools, frameworks, and best practices, this process heavily depends on specific organizational contexts and needs, which complicates developing and deploying a streamlined process across a given sector or business type. While broad frameworks such as IRIS+ and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a foundational set of key performance indicators (KPIs) from which organizations may select, the challenge lies in identifying which approach is most applicable, affordable, and feasible for each unique business. In many cases, organizations pull from multiple tools and frameworks or create their own, yet a multiplicity of tensions remain, as shown in Figure 1 from the guide.

As mentioned in the guide, “There is currently no standardization of climate impact reporting in the small business sector, leaving the burden on entrepreneurs to grow a successful business and implement the right tools to measure climate impact. Impact investors and entrepreneur support organizations (ESOs) likewise struggle to understand, use, and deploy climate metrics cost-effectively.” This challenge is particularly acute for enterprises addressing climate change adaptation and resilience. While companies focused on mitigation may center their reporting around carbon emissions, others struggle to find a single indicator, or set of indicators, that adequately captures their mission.

To further investigate these challenges and understand how organizations are navigating climate IMM challenges in practice, the ANDE team examined cases that are emerging in Southeast Asia, a region at a dynamic development crossroads: highly exposed to climate risk, yet also working concretely on the green transition, including but not limited to the increased adoption of renewable energy. For this project, the ANDE team spoke with impact investors, green fund managers, growing ventures, and one entrepreneur support organization (ESO) providing business development services that interact with over 300 companies and entities. Based on interviews with representatives from ATEC, ADB Ventures, The Incubation Network, and Insitor, ANDE identified trends that highlight what else needs to happen in the assessment space to make significant progress in the coming years. Example questions from interviews include the following: Are more tools or frameworks needed? Would third-party service providers that can customize IMM reporting at a low cost contribute to easing certain hurdles for some organizations?

Based on this research, we identified five key takeaways about the state of climate IMM in Southeast Asia.

INSIGHT 1: Climate impact reporting approaches differ depending on organizational intent, business model, and macro policy trends. In the case of for-profit ventures, investors are increasingly interested to hear about climate-relevant topics but are confined to business models that are proven and show a clear path toward profitability. This means that the sense of urgency and priority is susceptible to shift depending on whether climate impact reporting is considered by funders to be mission-critical or a nice-to-have. If the latter, then the climate IMM process is often more high-level and undetailed.

As one interviewee pointed out, “We don’t have the bandwidth and resources [for climate IMM], so we think, ‘Let’s use our resources for something else.’” Another interviewee observed, “When it comes to IMM, to be very frank, if it helps with the narrative and getting grants, people will want to capture impact… but everyone is very focused on resources.” They further elaborated, “it depends on who they are working with — for example, if they are working with policymakers… suddenly there is more interest.” From another anecdote, ANDE learned that the IPCC reports play a role in driving further investment into detailed reporting.

INSIGHT 2: Existing tools and frameworks like IRIS+ and the SDGs are helpful starting points, but customization is often necessary. Most interviewees touched on the major IMM frameworks, yet nearly all noted how customization remains critical. As expressed by one interviewee, “IRIS+ is a dashboard where I collect data and have the big picture, but then I have to go into greater depth for the company I am working with. I might look at a standard that I’ve never heard of before, and I have to do my own research.” Similarly, another interviewee mentioned, “Our internal framework is tailored to each country based on the specific country policy, yet we definitely adopt a lot of IRIS+ principles.” On the other hand, another organization shared that the type of IMM tool to leverage can very much depend on the audience, noting the need to go into more detail, “my sense is that the SDG [indicators] are more of a mass market lexicon,” rather than a framework that can provide detailed data.

INSIGHT 3: The climate IMM learning curve is steep, especially for organizations working without significant budgets to train their entire team. Some interviewees noted that the process of determining and explaining what to measure, why, and how is not straightforward and can be perceived to be relatively abstract by team members. As one interview revealed, “the most [difficult piece] is the challenge to understand — to break the [IMM] standards down into something understandable for our local managerial team.” Another interviewee shared, “There are a lot of local organizations doing great work, but they don’t know how to capture [the climate data] … and if I ask them to measure the kind of data that is needed, they don’t have the money or manpower.” How to demystify the space so there is greater clarity, consistency, and adoption remains a challenge, especially for resource-constrained organizations that span geographies, languages, and cultural contexts.

INSIGHT 4: Not all impact metric frameworks are fit for every context due to “lost in translation” moments, yet mitigation measurements are generally relatively straightforward. In some scenarios, the interviews surfaced that Global North-developed frameworks and tools do not always apply well across cultural contexts and capabilities. In these cases, the teams we spoke with noted how they often need to contextualize incumbent IMM tools and processes to make their own climate IMM more applicable to the field or situations in which they operate. For example, in some languages (e.g., Vietnamese), the “conditional tense” does not grammatically exist, so if one were to ask in English, “On a scale from 1 to 10 would you say this product or service reduces climate change risk,” the interpretation and subsequent response recorded may not reflect the actual felt sentiment.

In contrast, as noted in another conversation, “for things that are very quantifiable, there isn’t much of a concern… the tricky part would be the ‘social’ elements within the climate space.” The interviewee explained that, in the waste sector, a global IMM reporting framework may fail to explain how to define and differentiate informal waste workers from formal ones — leading to inconsistencies in reporting across jurisdictions. “There are a lot of ways to see this. How do we translate the questions into something [applicable and] local?”

Another interviewee went further to say that when it comes to applying a climate IMM lens to adaptation and resilience work, “It is a bit trickier. There are more assumptions in terms of reaching communities that are vulnerable to climate change. Sometimes it is objective and [sometimes] more subjective in terms of defining and measuring and monitoring which groups are really vulnerable.” Alternatively, in mitigation work, “frameworks are more developed and, essentially, it’s quite scientific.” This validates insights surfaced by ANDE’s climate guide, which identifies adaptation and resilience as a key area for further development. Adaptation and resilience solutions frequently span multiple sectors, such as crop insurance against drought, flood-resilient homes and building materials, or water reclamation. Because of this diversity, it can be difficult to develop a framework that can be applied easily across different contexts. Mitigation, which involves measuring the amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions avoided, has well-developed estimates and resources.

INSIGHT 5: Learning how to catch assumptions, even with data that is climate and environmentally oriented, is critical. Across the conversations, one of the key patterns that emerged is the need to be extra cautious about the type and quality of data that can be directly collected and accounted for, versus that which is inferred or projected. As a hypothetical example, if an impact venture is able to replace conventional motorbikes on the road with electric motorbikes, is it possible to project calculations about the quantity of carbon emissions saved or removed? As some interviewees noted, it is not easy to gauge the precise behavior of an end customer or user, which concerns some organizations regarding the use of proxy estimates or indicators. Interviewees flagged that these types of estimations should be accompanied by documentation that clearly articulates the process to avoid generating exaggerated and misleading impact claims. While there are mechanisms to assess utilization, such as life cycle assessments for transportation solutions, not all ecosystem actors are aware of these resources or know where or how to access them.

What’s next? Remaining questions and areas for continued research

→ Combat greenwashing and create opportunities for third-party support. Nearly all interviewees expressed some level of trepidation about how climate IMM is vulnerable to greenwashing. Claims around climate impact can benefit from more third-party monitoring and verification that is both transparent and able to be implemented cost-effectively. When asked about the dynamics of third-party impact verification, one interviewee noted, “We don’t have the resources for an impact verifier to walk from family to family and count.” However, technology has become available that can confirm climate impact in new ways that reduce risk and increase trust. Most interviewees mentioned that they had an interest in or maintained existing collaborations with third parties that function to design, monitor, or verify their work. This was notably important for public-facing climate IMM work. The World Bank offers an example of a developed verification process for carbon credits, which can serve as a guide for the verification of other climate outcomes.

In a similar vein, it was also noted that, “there is a lot of confusion in the industry now around environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings and impact investing,” and that “to avoid greenwashing, it comes down to certain principles and consistency. Everyone understands that there is a degree of subjectiveness, [yet] we publish a theory or change the assumptions; everything is very detailed in the footnotes: what are the assumptions, the sources of the data.” This underlines the importance of transparency and detailed reporting as another method to prevent greenwashing and exaggeration of impact in the sector.

→ Disaggregation of data is increasingly critical, but capacity continues to be a constraint. Many businesses and organizations are not fully set up to capture various bespoke insights. As one interviewee expressed, “When I ask, for example, can you please disaggregate by gender the number of customers? The entrepreneur feels overwhelmed by this request. So imagine if that already is overwhelming. Having to find the formula to measure a climate-related metric can be difficult.” Different tools or free services to entrepreneurs for measuring climate IMM is a need and opportunity for small business support organizations.

→ Top-down influence from large corporations can play a role in advancing climate IMM. In terms of trends on the horizon, an interviewee noted, “one factor that is really going to drive the [climate IMM space] is the actual industry and corporations who will have an impact on the startups and policy… this will change the landscape, of course.” The interviewee went on to further explain, “all of them have made commitments to decarbonize their supply chain and make it green and carbon neutral. [And] because the corporations have commitments to their shareholders, you know, over time, they will have to have robust systems to track that.” Standardizing supply chain climate impact reporting may result in positive pressure down the value chain to smaller businesses to expand their own measurement.

Naturally, the above insights underscore the notion that there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to climate metrics, yet the fact that organizations are grappling with the various standardized principles and available tools signals that the climate impact and measurement field is indeed evolving. While organizations around the world are still discovering the best-fit tools and frameworks to measure the climate impact of the businesses they support and invest in, it is important to stay close to the practitioners working in real time.

In this spirit of learning and exchange, more detail is given below about the organizations interviewed and their climate impact journeys.

Southeast Asian organizations’ impact journey highlights:

ATEC

Social Business, Cambodia and Bangladesh

ATEC aims to solve clean cooking globally by delivering modern, affordable IoT cookstoves and digital carbon credits to emerging market households. Their patented eCook is the world’s first pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) induction stove, bringing together PAYGO, Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), and Internet of Things (IoT) functionality to make mobile money payments easy for unbanked or financially underserved populations and provide real-time user information. At the same time, ATEC is also working on generating carbon credits and accelerating climate finance by leveraging real-time user information to validate avoided emissions. In turn, this revenue helps offset the cost of the stoves to base-of-pyramid (BoP) households.

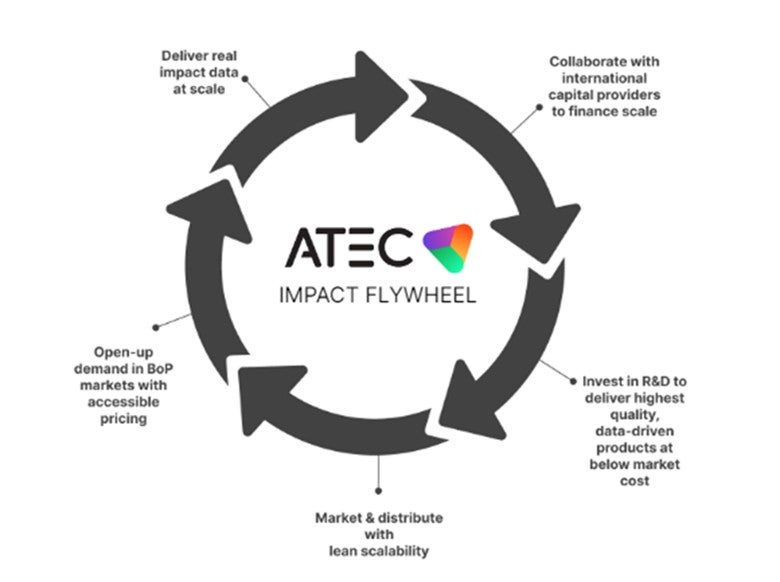

ATEC started its IMM journey by using the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a strategic compass to orient its staff and express what kind of impact they were able to generate. As the team expressed in the interview, “We understand and believe in the SDGs, and we believe it’s a fantastic framework.” At the same time, the company created the “Impact Flywheel,” an impact model that helps its teams anchor their work as well as support the ways in which they articulate their core businesses to customers and investors alike.

In their own words, they shared, “ATEC’s unique Impact Flywheel is the strategic core of how we solve clean cooking. Through creating scalable partnerships between BoP households and international capital markets, our flywheel enables ATEC to offer high-quality, low-cost IoT stoves to BoP markets at scale. With each stove automatically validating carbon credits up to 10 years, ATEC decreases upfront costs for consumers, which further increases sales and credit revenue.”

Image provided courtesy of ATEC

The company’s impact collection and management system has been evolving over time. One of its latest endeavors has been in collaboration with The Gold Standard, an initiative established in 2003 by WWF and other international NGOs that functions as a verification process for carbon reduction projects, programs, and business products and services like ATEC. Additionally, to supplement the IMM process, ATEC is also working with Climate Impact Partners, also known as Climate Care, to produce a more rigorous and third-party-verified system for their work.

Contributors: Nikolai Schwarz is the Cambodia Country Director and Monika Noshin is the Funding Coordinator of ATEC.

The Incubation Network

Entrepreneurial support organization (ESO), Singapore

The Incubation Network is an impact-driven initiative aiming to prevent plastic waste from flowing into the world’s oceans. They are Singapore based, yet work regionally with 300 solutions-focused businesses and organizations to orchestrate and amplify connections between entrepreneurs, policymakers, decision-makers, and investors. They strive to advance the circular economy by supporting startups across all maturity stages and scaling their early-stage or pre-investment innovations together with key industry stakeholders. Established in 2019, The Incubation Network is a partnership between The Circulate Initiative and impact innovation company SecondMuse. Representatives from The Incubation Network shared, “What we do revolves around building ecosystems to ensure there is equity with the actors involved… we try to work around intersectionality so [while] the specific program revolves around the issue of plastics… we are not only thinking about what plastics we can take out of the system, we are talking about the workers, the people involved.” By taking both a systems and climate justice approach, The Incubation Network examines not only waste management but also the empowerment of waste workers. This expanded scope further emphasizes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to climate IMM.

Photo provided by The Incubation Network

Photo provided by The Incubation Network

The Incubation Network leverages several existing tools and frameworks, including IRIS+ and the SDGs, among others. As pointed out in the conversation, “we look to The Circulate Initiative (a core partner with deep expertise in the space) for guidance on what degree [of specificity and] to what level we can measure things.” In terms of more emergent frameworks that they also draw upon, TIN mentioned The NextWave Plastics Framework for Socially Responsible Ocean-Bound Plastic Supply Chains as a helpful resource. As noted above, much of the approach to data collection must be contextualized, especially for ESOs that work with hundreds of diverse partner companies and organizations in their network.

Contributors: Joshua Foong is the Evaluation Specialist for SecondMuse, the parent organization of The Incubation Network

ADB Ventures

Development Bank Program, Philippines

ADB Ventures is the venture platform of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), focused on investing in early-stage technology companies generating climate impact in emerging Asia. It provides seed and early-growth stage capital, in addition to offering access to extensive networks, sector-specific insights, research, and a platform for expansion into new markets. According to ADB Ventures, “We invest around the theme of how to decarbonize and green industry and supply chains… as over 50% of global CO2 emissions is coming from Asia, particularly from developing Asia. ADB is therefore working with governments and the private sector to mobilize finance and cutting-edge knowledge and technology innovations to tackle climate change.” As one of the pioneers of climate tech investing in Asia, ADB Ventures has a key role to play in climate impact measurement. As a first step, it identifies the impact linkage of the business model and the pathway to climate mitigation and/or adaptation. To design specific climate metrics, it adopts its existing in-house frameworks that are then tailored to early-stage technology companies. ADB Ventures’ approach to climate IMM is a combination method. It leverages established internal core IMM methodology and processes but has adapted and evolved the same on its journey of working together with early-stage investees to determine the most relevant and measurable indicators.

Photo provided by E Green Global

Photo provided by E Green Global

The climate IMM strategy has come from a learning and reflection process over time and is maturing as ADB Ventures’ portfolio reaches over 40 companies. As ADB Ventures noted, “In terms of the lessons learned, we definitely learned a lot. When we started, we maybe tried to collect too much information… though it doesn’t make sense to have an elaborate IMM at the very early-stage life cycle of technology companies. Instead, we focus on assessing the potential impact by getting a handle on the unit impact and ensuring that [the venture’s] core business model is aligned to climate impact and we try and keep it relatively light touch.” The team noted that as their portfolio startups grow and scale, the ADB Ventures team can revisit key assumptions and gather additional data to validate impact and invest more resources for IMM, including impact audits of successful investments that contribute meaningfully to fund-level impact targets.

Contributors: Dominic Mellor is the Co-Founder of ADB Ventures.

Insitor Partners

Impact Fund Manager, Singapore

Insitor is the first impact fund manager to set up operations in Southeast Asia and a pioneer investor in India and Pakistan. They have been working to create synergies and share best practices and industry expertise, especially by taking a long-term development approach to the countries where they operate. Insitor’s portfolio companies have directly reached over 51 million underserved consumers and focus on the impact intersection of multiple SDGs. Insitor is also a signatory of the Operating Principles for Impact Management, a framework developed for investors to consciously and purposefully integrate impact considerations across their investments. They have used the Impact Measurement Project (IMP)’s suggested tools and have invested by using a robust ESG framework for several years.

Photo provided by Insitor

Photo provided by Insitor

In their own words, they shared how climate considerations are integrated through their IMM approach, “we have an impact thesis, which is that of investing in entrepreneurs that are providing services and goods to low-income families [who] wouldn’t be able to access or afford them otherwise. We have three main themes that we invest in: economic growth, better health, and sustainable living. So while we target these themes of social impact in our key groups, the climate aspect is a byproduct of what we do. In sectors like health, we, for example, look at a family switching from kerosene to a solar home system to provide household lighting. Health is the main impact that the new service for lighting is providing, but at the same time, we recognize that there is a climate impact as well.”

Looking forward, Insitor feels that climate considerations are being put more front and center but recognizes that there is still work to be done. Significantly, entrepreneurs are increasing their capacity to be able to provide investors with relevant impact information.

Contributors: Francesca Puricelli is the Director of Impact and Sustainability and Bradley Kopsick is the Country Director (Myanmar and Cambodia) for Insitor Partners.

The research conducted for this blog post was generously funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views expressed are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian Government.

For more information, please contact Mallory St. Claire at mallory.stclaire@aspeninstitute.org